|

| TWWW1965 |

PART ONE: SETTING THE STAGE

Thanks to a classic case of being in the right place at the right time, I found myself as low man on the totem pole in Glamour Magazine's art department in 1965. Read on if you are curious (or nostalgic) how magazines were put together way back when.

Perhaps you should rent "Funny Face". While we never burst into song (especially about pink), that movie captures the spirit of making a fashion magazine. It was always "Let's put on a show"— serious business that was nevertheless a melange of make-believe, let's pretend and dress-up.

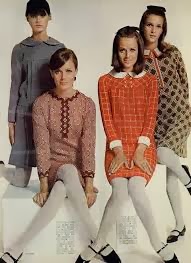

The sixties were pivotal times for fashion, yet in 1965 we still wore gloves to work, no bare legs ever and no pants to the office. But you could hear the Youth Quake coming; New York and London were the coolest places on earth.

Glamour Magazine was (and still is) Conde Nast's cash cow. The magazine was thick with ads (always the sign of health) and enormously influential in the industry and the demographic it served— college women, those new to the work force and young marrieds. It had been my favorite magazine from junior high on. Before I worked there I knew every name on the masthead and all the photographers, models and illustrators.

Glamour's offices were on the 19th floor of the Graybar Building at 420 Lexington, a lovely art deco pile attached to Grand Central Station at 43th Street. Glamour shared the floor with Vogue, but not equally. You could see the Vogue reception area from the elevators. Glamour (no receptionist) was past the photostat studio. The hallway dead-ended; editorial to the right, advertising/promotion to the left. There may in fact have been more staff running the "business side" of the magazine, but our paths crossed rarely.

|

| The Graybar Building |

The Glamour art department had banks of windows facing north and east. It was a large room with space for three full-time staffers to work: Shirley, jack of all trades but specializing in production and schedules, myself as Shirley's helper/fledgling designer. There was also an assistant to art director Miki Denhof, who worked closely with her on the major parts of the magazine. Miki had an adjoining office, which she shared with her secretary, Mary Anne.

We worked standing up at a central island. There were no partitions thus no privacy (for phone calls or wasting time). We pretty much knew everyone's life stories. There were bins and drawers and cubbies all around for the multitude of art supplies needed, including sheets and sheets of "dummy type" to cut and paste in place on the layouts.

Although we had trash cans, the modus operandi was to throw scraps on the floor and let the cleaning crew sweep them up— a very bad habit that I eventually took home with me. There was no room to keep anything personal by your workspace. Shirley tended to a veritable jungle of plants on the window sills, including years of avocado seeds now sprouting towards the ceiling.

Shirley was a native New Yorker who'd worked at Glamour for years. She and her husband had an apartment on 57th Street and lived what I thought was the quintessential New York life— entertaining, theatre, museums and art galleries. An excellent cook, she was my go-to person for advice. Shirley regaled us with her culinary adventures, which included serving rabbit to dinner guests and diffusing the question as to why the chicken had so many legs. At Christmas we established a department tradition where, instead of buying individual gifts, we pulled names attached to a wish list with a $25 limit. The only thing Shirley wanted one year was a white truffle, then going for $25 an ounce at Bloomingdale's. FYI an ounce of white truffle today goes for $199.

The assistant art director worked opposite me, across the island. First was Gerry, a handsome man who always wore a suit and tie (thanks to him I can tie a Windsor knot). He emigrated to Australia, which was offering professionals a $1,000 bounty if they remained a year. Gerry passed me his rent-controlled apartment on West 10 Street— still a gorgeous block today. The apartment had a fireplace, brick walls and built-in bookshelves and was fabulous (except for the four flights). Next came Ben. He left for greener pastures (probably in advertising where he could earn a decent paycheck). George, a previous assistant, returned with great fanfare and eventually became Miki Denhof's successor.

There was always the assumption you had to afford to work at Conde Nast. Salaries were notoriously low and did attract a well-educated trust fund type waiting for Mr. Right. But there were plenty of us who loved what we were doing no matter the remuneration. We were proud to work for Conde Nast.

We did work— those scissors flew all day long. Although, when I think about it— how much work did we actually do? The workday was 9 to 5, although it was alright if you got in before 9:30. You did want to make it before the free coffee cart was rolled away at 9:45. There wasn't a lunch room or break area. It was okay to eat at your desk, ostensibly while working, then go out for another hour. We in the art department may have worked till 5:30. By that time all the other offices were silent and dark.

The three-martini lunch was not part our day. Mrs. Denhof always lunched at her desk (and never left the building). One of her secretary's duties was to order lunch from the Gourmette Delicatessen. The order was always the same— black coffee, hard boiled egg, fruit salad. It was then "decanted"— wrappings removed and the food placed on a tray set with black lacquer dishes and real silverware. If Mary Anne was out for lunch or on an errand, the ritual fell to me.

Miki Denhof (whom I never called anything other than "Mrs. Denhof") was one of the first female magazine art directors. She had been Alexander Liberman's assistant at Glamour before he moved to Vogue, and Alex remained her mentor. Miki had been born in Trieste and fled to the US in 1938. I had been cautioned about working for her, "You won't like her; she's tough". That quality, plus being fair, made her an excellent boss. She was very clear in telling you what she wanted. If you got it right, you got thanks. If you missed the mark, you had the chance to try again. She encouraged your ideas, but only after you did what she asked first. When you earned praise, it meant something.

Mrs. Denhof rarely had time to design layouts in the office, but she took work home. The layouts she brought back were covered in dried rubber cement. It was my job to clean them up, collecting great wads of rubber cement balls we joked about setting on fire. In cleaning up Mrs. Denhof's layouts I believe I learned to design by osmosis. Whether intentional or not, it was a great teaching technique.

One summer I had the opportunity to visit Europe for the first time. When I told Mrs. Denhof, she was excited for me. Then I broke the news that the charter ticket was for a month, and I needed to take two additional weeks. She said, "My dear! Of course! One cannot go to Europe the first time for anything less than a month!"

Continued in Part Two (sooner rather than later I hope)...

What a wonderful reminiscence! I love "Funny Face" - how marvelous that it was much the same for you.

ReplyDeleteHow interesting! Your life really does sound "glamorous."

ReplyDeleteHope you enjoy Part Two because it's coming!

ReplyDeleteMichelle! Hello!

ReplyDeleteI wondered who wrote this.

Mrs.Denhof...Shirley...George!

Thank you so much for this memoir.

How I loved working with Mrs. Denhof. Such a pleasure to remember her. In 1969, unbeknowst to me, she had discovered my illustrations in Harper's Bazaar. When I called to make an appointment to show my portfolio, she got on the phone and said, "Hello, I was just looking at your work in Bazaar. How would you like to work for us a lot?" And so I did.

Those were the days..I am glad I had the chance to work with you for so many years.

I hope you are well & happy.

I was just thinking about Mrs Denhof and decided to google her...and I found you too.

Best wishes

Catherine Siracusa

Hello: I'm trying to see if I can be in contact with the author of this post on Miki Denhof and Glamour magazine. I'm a professor of art history and trying to get more information about Conde Nast & Glamour in that period. If you're open to it, I can be emailed at:

ReplyDeleteml2450[at]hunter.cuny.edu

Thank you!